12/2/17 What I Think About Henry Mayhew

‘A picture of life so wonderful, so awful, so piteous and pathetic, so

exciting and terrible, that readers of romances own they never read

anything like to it.’ This was Thackeray in 1850, on reading Henry

Mayhew’s ‘Labour & The Poor’ columns in the Morning Chronicle newspaper. Mayhew’s reports on the living conditions and earnings of

London street folk give new force to the hackneyed notion that truth

is stranger than fiction. Those who have ever considered that Charles

Dickens twisted the everyday into fantastical and monstrous shapes for

sensational purposes must re-think their position after the briefest

dip into Mayhew.

City life had coerced the poor into adopting the most

elaborate strategies for scavenging a bare living; and the ingenuity

of their entrepreneurialism, the tenuous nature of their hold on life,

their suffering, stoicism but also the pure belly-laughs of their

world tumble from every page of Mayhew’s reports, which he expanded in

1861 into four book volumes. The corn-salve seller exhibits what he

claims is a large corn ‘from the honourable foot of the late-lamented

Sir Robert Peel’ — ‘a Free Trade corn’, he calls it during his

patter. Dick the Dollman hides the legs of his substandard wares as he

touts them, because they make the dolls look gout-ridden, being

'rather the reverse of symmetrical’. The man reputed to have invented

writing that runs the length of a stick of confectionery sells one

that reads ‘Do you love me?’, another, less romantic, ‘Do you love

sprats?’. 380 false eyes gaze Mayhew into perplexity as the

false-eye-maker reveals the details of his trade. Non-existent crimes,

such as The Scarborough Tragedy, and The Chigwell Row Murder, keep the

vendor of cheaply printed ‘news’ from cold and hunger, while another

such admits that he has earned good money by killing off, in print,

the Duke of Wellington (twice), breaking Prince Albert’s arm and

having the Queen give birth to triplets.

This is a world of the fake, phoney, substandard and unregulated. It’s also a world of extreme recycling, where any object can be scavenged, patched-up and sent out into the world to earn a

not-necessarily-honest penny. Even dog faeces had its price (sold by

its lucky finders to tanners), while the velveteen-coated ‘toshers’ roamed the sewers in search of items to salvage and sell on.

So the question does have to be asked — to what extent was Henry Mayhew a polisher-up of dull testimonies? It’s a matter Robert Douglas-Fairhurst does not duck in his introduction to the new OUP selection from Mayhew. Douglas-Fairhurst decides that little varnishing took place, and that what Mayhew’s survey presents to us is ‘at once a towering historical record and a suggestive inquiry into cultural myth-making’. Human beings are story-telling creatures, and it was the interviewees, rather than Mayhew, who incorporated urban folklore into their already grotesque daily lives. There may not have been wild swine roaming the sewers of Hampstead; but if you spend your life down there, the notion that there may be becomes part of your everyday reality.

Mayhew was working within the reasonably lucrative genre that catalogued the lives of London’s street poor. Picturesque and bizarre beggars and hawkers, as well as crooks and conmen, had been described and illustrated for the market since the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Select Committees, statistical societies, agitators for change (from Chadwick to Engels) kept the indigent in full view too, in the 1830s and 40s, and many a novelist spliced scenes from ‘low-life’ into their cityscapes. There was little new about the subject matter. Mayhew’s innovation was to let the poor speak for themselves at length — to self-define, rather than sticking to a narrow agenda set by the questioner. And where other interrogators would cut out their extemporising, Mayhew recognised that the marginalia of the interviewees' conversation was where the true meaning of their lives often lay. That is why he is still read today, while his predecessors, and many of those whose writing he influenced, are little known except to those who specialise in such material.

It is Mayhew, to a greater extent even than Engels, who reveals the processes of a highly complex society where capitalism has come to maturity. Cumulatively, the interviews suggest the structures against which individual poor Londoners fashioned their lives — or failed to do so, and perished. But Mayhew's ongoing appeal also partly stems from his non-alignment with any political theory — or rather, his brief flirtations with various ethical postures, adopted and abandoned within the space of a few paragraphs. He is the man of the crowd, and his shifting moods, ranging from intense empathy to utter disgust, make his work feel more trustworthy rather than less.

He stated at the end of his preface that his aim was simply to alert the rich to the sufferings of the poor, to urge them to ‘bestir themselves’ to improve the conditions of the people — he did not say how, but somehow stimulating ‘self-help’ seemed to be what he had in mind. Evangelical philanthropy, however, was not the way, as it patronised and robbed the poor of the admirable spirit of endurance (their most attractive feature, as he saw it). He thought protectionism was a good thing: he believed Free Trade suited the capitalist but protectionism suited the working man, as a defence against the mid-century’s mania for cheapness. Cheap goods always meant cheap labour; cheap labour usually meant poverty.

Today’s right and left can both claim Mayhew for their own, if they

read his investigative findings selectively. Two thousand interviews

totalling 1.7 million words (in the unabridged work) speak eloquently

for themselves about the devastating level of human misery and

injustice that arises when laissez-faire runs amok and charity is the

only ameliorative power. However, Mayhew himself stated at the outset,

‘I shall not be misled by a morbid sympathy to see them [the poor]

only as suffering from the selfishness of others’, and elsewhere, he

despaired of ‘men whom, for the most part, are allowed to remain in

nearly the same primitive and brutish state as the savage — creatures

with nothing but their appetites, instincts, and passions to move

them’.

Anti-Welfarists can point in these pages to the resilience and ‘character’ that develop under adverse economic conditions, and it

remains to be seen to what extent our government will continue to create the

conditions in which poverty can flourish so that we may stand back and

admire the nobility with which extreme suffering is borne.

This originally appeared in The Literary Review as a review of a new edition of Mayhew, London Labour & The London Poor: A Selected Edition, edited by Robert

Douglas-Fairhurst

(Oxford University Press, £12.99, hardback)

13/1/17 Plagiarism, television and non-fiction writers: my letter to the Society of Authors

I wrote this piece below for the Society of Authors’ magazine The Author after having had my work appropriated by yet another television production company. I and a number of other non-fiction writers are hoping to get a set of good-practice guidelines established and are seeking to hold a panel discussion this summer at which authors, agents, publishers and lawyers can debate how best to tackle this growing problem. Jo McCrum of the Society of Authors would like to hear from you if you are a non-fiction author who has been affected by this issue. You can contact her on jmccrum@societyofauthors.org (you do not need to be an SoA author in order to do this).

‘There is absolutely no factual basis whatsoever for any of your

ludicrous claims...Your comments are clearly defamatory of my

client... The claim of plagiarism is not only defamatory but itself

can only serve to bring you into disrepute...

First letter before action’

I’d never received a letter like that before. It was sent by the agent

of a television scriptwriter, after I had mentioned on Twitter that

the scriptwriter, whom I did not name, was thinking of adapting one of

my non-fiction/history books for the screen, but instead had taken an

aspect of the book and developed a present-day narrative that made use

one of my book’s themes. I knew all this to be the case because the

scriptwriter had said so himself in an interview in a magazine. I was

only repeating what he had admitted. And I never used the ‘P’ word –

that was all in his imagination.

I’d thought it extremely odd, while reading the interview, that an

attempt to adapt a book of mine for the screen had gone ahead without

either me or my agent knowing anything about it, and certainly without

an option being drawn up. I’ve had non-fiction books optioned twice

before and that was a perfectly straightforward, civilised process by

which, respectively, the BBC and ITV had secured temporary sole rights

to adapt two of my books. I had assumed that that was how it always

worked.

But I suspect a worrying trend may be developing that will rope off

yet another pathway by which non-fiction authors can earn some money

from their own work (no, I’m not going to call it ‘content’). And I’m

writing this article to kickstart a debate that I think is long

overdue: what can non-fiction authors do if their books are

commandeered by telly folk without their agreement or even knowledge?

I know, the obvious answer is ‘sue’; but that is a daunting prospect

to those of us who simply cannot afford to risk losing a case no

matter how much moral right we may have on our side.

That ‘First Letter Before Action’ unpleasantness was actually third

time around for me. Previously, a TV award-winning series leaned

heavily for one of its episodes on one of my books. The producer had

contacted me and I had helped out by answering questions by email and

contacting potential interviewees for him. I had asked for no money in

agreeing to help out; but when, with filming completed, I asked if I

could have a screen credit as a consultant, the request was treated as

problematical. Far worse, the series’ tie-in book précis-ed my book for one of its chapters, cleverly kicking over the traces by including

no endnotes and no bibliography, thereby passing its contents off as

fresh archival research on the part of the writers.

More recently, I was asked to be a paid consultant, for a modest fee,

on a historical series, only to discover when the scripts were

delivered that one of the episodes closely shadows a book of mine. The

episode in question uses the same (rare) archival testimonies and

historical witnesses, in pretty much the order in which I present them

in the book, and echoes my conclusions as to what the testimonies

might mean.

I explained that I was unhappy about this, and that the full option

fee would have been more appropriate than a small one-off consultancy

fee; but the large and very wealthy production company has not budged.

These facts are ‘in the public domain’, they said; you don’t own the

past, they said, and so we can make use of all the sources you listed

in your bibliography because you have no exclusive rights to archival

material.

So what do we think, folks? And what can the Society of Authors

suggest we do? For fiction writers, plagiarism cases are easier to

assess. But for those of us who take years (yes, I’m serious)

carefully piecing together reconstructions of often deeply hidden

histories, our work — it would appear — can simply be appropriated by

others for no fee and no credit. This strikes me as profoundly wrong;

and, more practically, as yet another hit on the incomes of

non-fiction writers, at a time of plummeting advances and expectations

that we will give talks for diddly-squat.

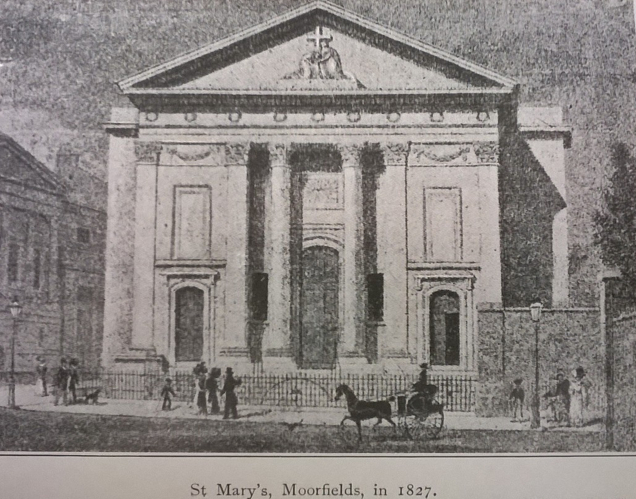

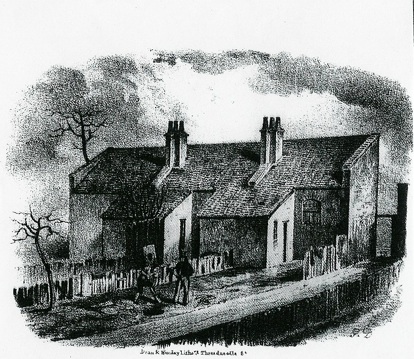

13/8/16 St Mary Moorfields, Roman Catholic chapel

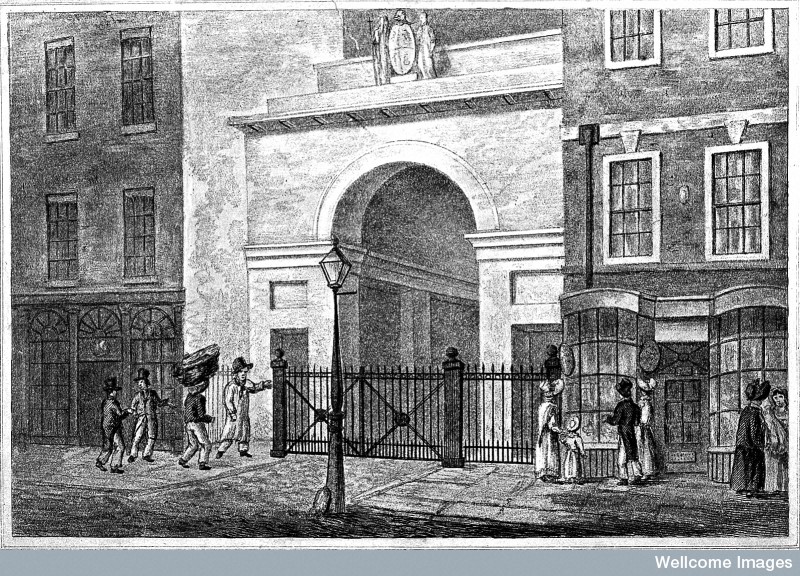

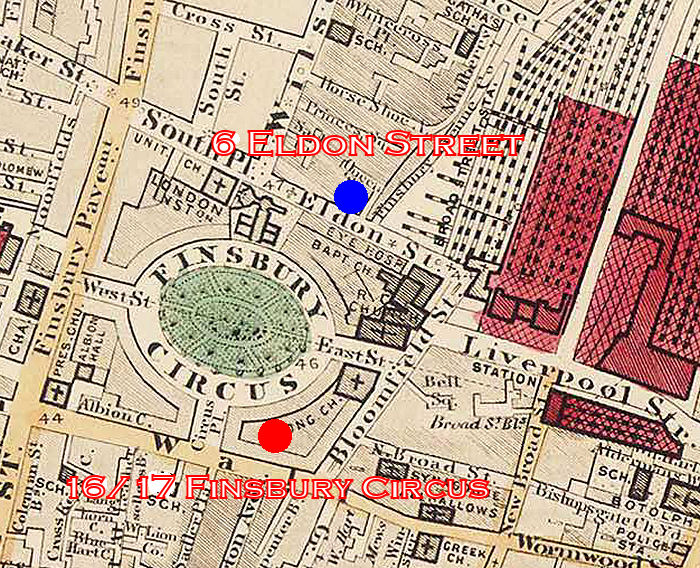

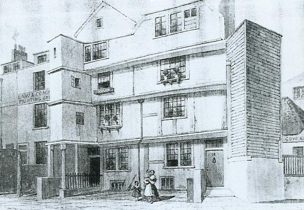

The ‘fourth man’ in the Italian Boy case was Michael Shields, a gravedigger turned carrier for bodysnatchers. Though released without charge, Shields was well known in the bodysnatching community as a strong, reliable and discreet porter: he ferried corpses around London in a large straw basket placed upon his ‘porter’s knot’ on top of his head.

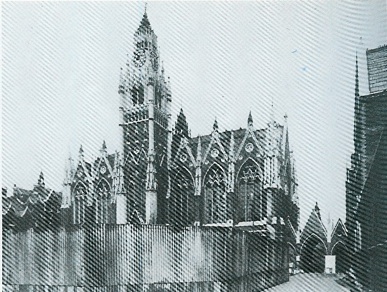

He had previously worked as a careaker for St Mary Moorfields Roman Catholic chapel, but was dismissed for stealing church silverware. St Mary Moorfields is pictured below in 1827, in its Finsbury Circus incarnation. It had opened in 1820 and stood on the north-east corner with Blomfield/Bloomfield Street. Next, Shields went on to be a fruit, veg and flower porter at Covent Garden market, as well as a gravedigger at St Giles-in-the-Fields; from there, it was a sideways step into transporting around town the bodies dug up by resurrection men.

Below is a contemporary sketch that did the rounds during the Italian Boy trial, showing Shields turning up at King’s College in the Strand on 5 November 1831 with John Bishop, Thomas Head and James May; he was delivering the corpse that would lead to the four men being arrested. Shields was released from Bow Street magistrates’ court as there was little interest in pursuing this lesser charge when it appeared that the Italian Boy case was in fact a major multiple murder inquiry.

St Mary Moorfields was demolished in 1899 (when the interior, below, was sketched) and moved to new premises in nearby Eldon Street, where it still thrives.

You can read more about the present-day church here www.stmarymoorfields.net

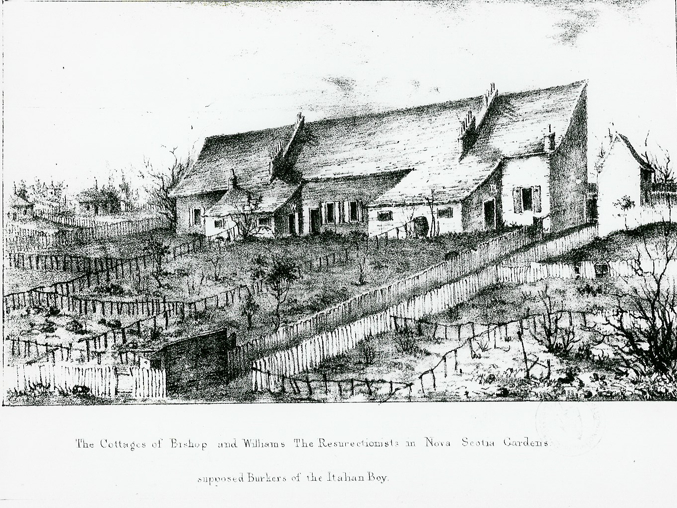

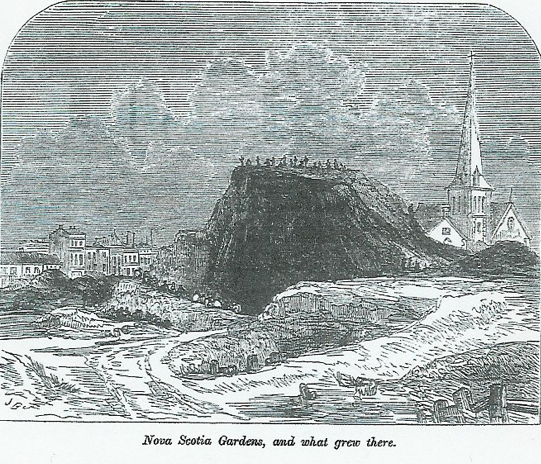

9/11/15 And ANOTHER view of Nova Scotia Gardens

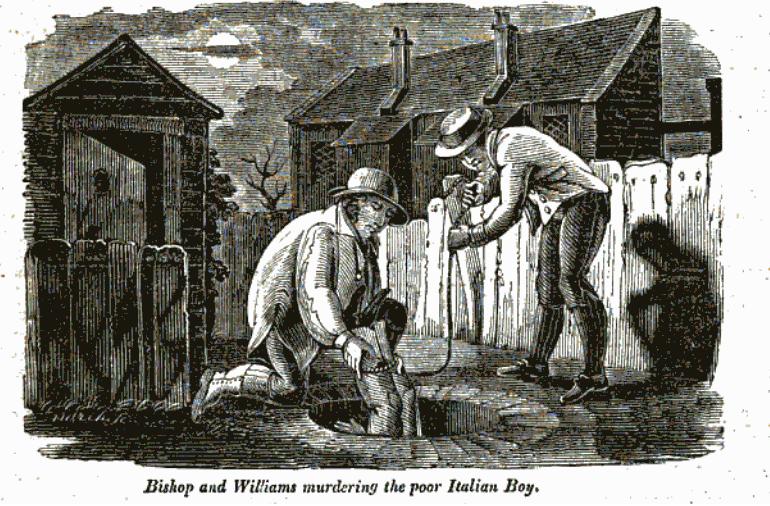

This illustration of the killing of the Italian Boy appeared in the Annals of Crime for 1831, and it even features the mysterious lavatory that stood at the end of Bishop’s garden. (Seriously unpleasant...) See several of the stories below for other artist impressions of the scene of the crime.

26/8/15 The fat little cherub at Pye Corner

Rob Baker tweets the most fantastic London pictures (find him on Twitter at @robnitm). He recently posted the one below (dating from 1966).

The Golden Boy stands at what used to be known as Pye Corner, at the junction of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane, opposite St Bartholomew’s Hospital (seen on the right of the picture).

In the picture below Rob’s, here’s one I found dating from 1910, of the shortly to be demolished Fortune of War pub – safe haven and watering-hole of the London bodysnatchers – with the Golden Boy on the Giltspur Street side. At this time, he was simply made of gilded wood, and by 1910, his original yellow-painted tiny wings had been knocked off. (For my money, he looks rather more thoughtful than his later incarnation.)

The Fortune of War had originally been called The Naked Boy pub, and the figurine is far older than the tavern. In 1721, the new publican changed the pub’s name, allegedly because he had lost both his legs and one arm at sea: the ‘fortune of war’ was loss of limb, literally. A rival story has it that a prize fighter bought the Naked Boy with the winnings from his boxing and changed its name – using the fortune he had made from ‘war’ in the ring.

The latest, very bright gold, version of the boy can be seen today on the wall of the 1980s office block that’s on the spot. Below him, there is also a fresh version of the legend carved into stone, telling the story that the Fire of London stopped at this spot in 1666, and claiming that the Fire had been caused all along by gluttony, debauchery and so on. . . But especially gluttony, because it started in Pudding Lane and ended at Pye Corner. Geddit?!

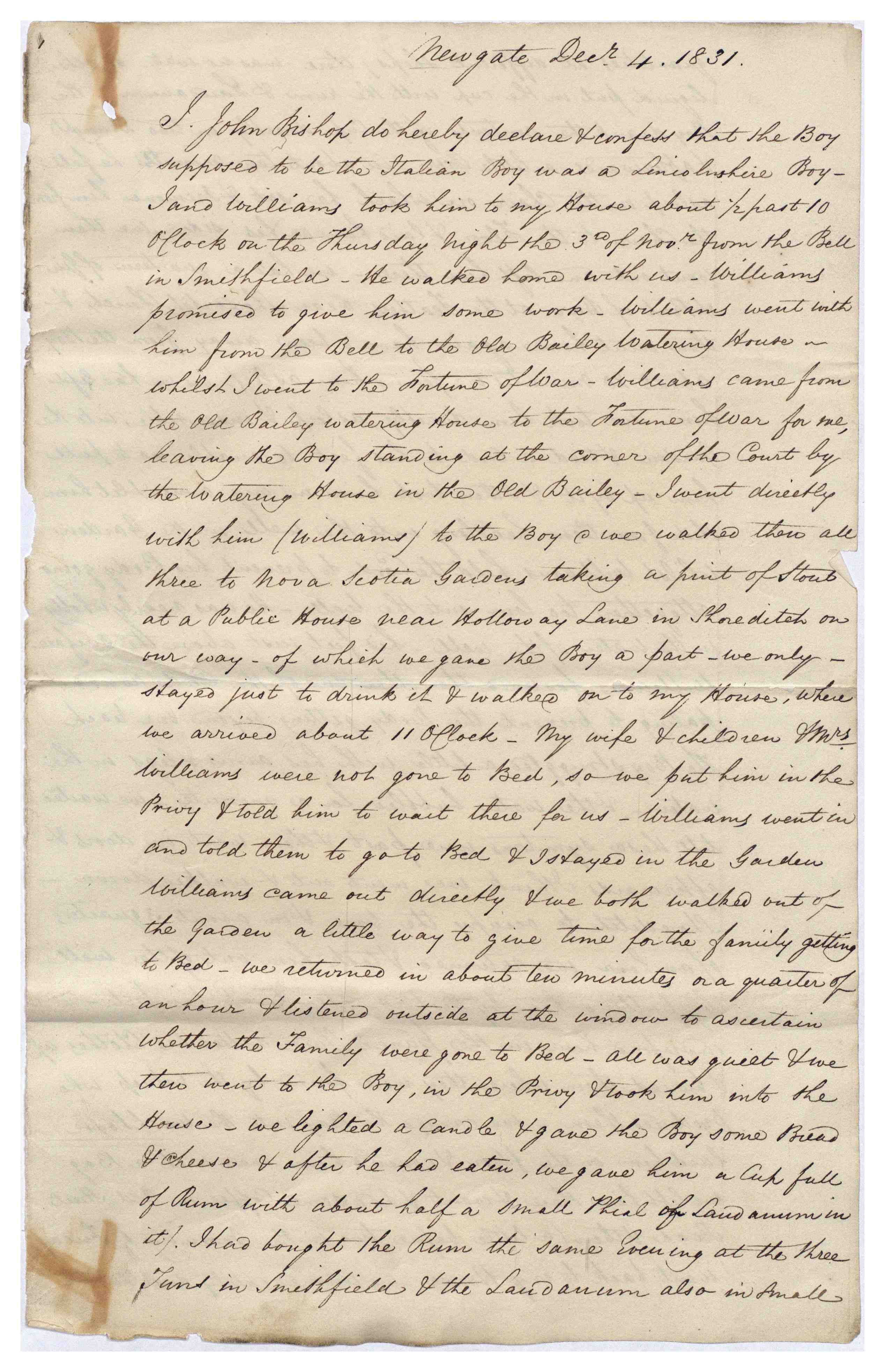

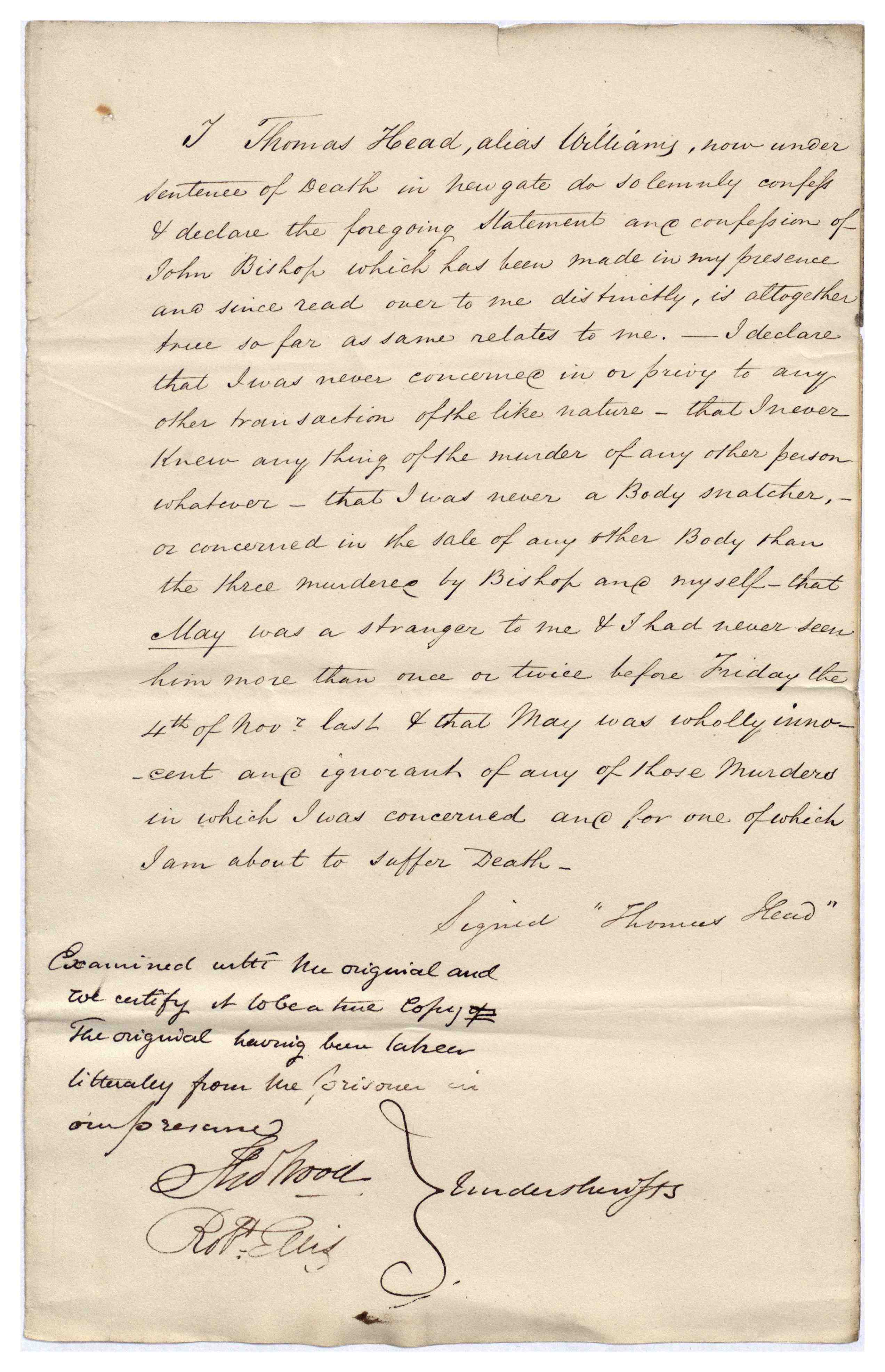

17/7/15 SPOILER ALERT! The Newgate confessions of John Bishop and Thomas Head

[If you’ve not read The Italian Boy, this post tells you who done what to whom...]

On the day before their execution, the killers of Carlo Ferrari at last revealed how they had inveigled him to their home and killed him. These original documents are in the National Archives at Kew, shelfmark HO17/46/6Q/70.

The handwriting is that of the chaplain (also known as the ‘Ordinary’) at Newgate Prison. Below are page 1 (of 14) of Bishop’s statement, and Thomas Head’s one-page confession.

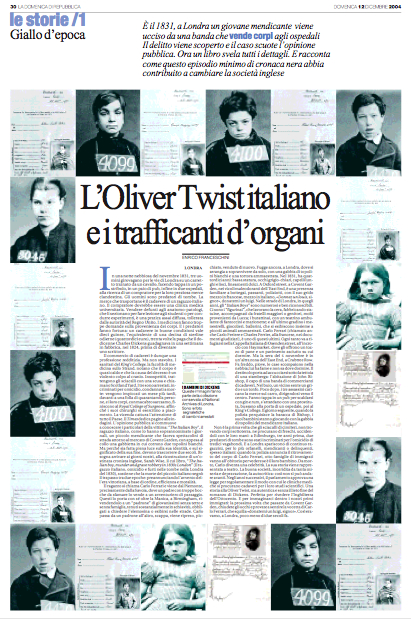

Oliver Twist and the bodysnatchers: a review from the Italian newspaper La Repubblica — in Italian!

‘L’Oliver Twist italiano e i trafficanti d’organi’

‘Londra in una notte nebbiosa del novembre 1831, tre uomini girovagano per le vie di Londra su un carretto trainato da un cavallo, facendo tappa in un postribolo, in un paio di pub, infine in due ospedali, alla ricerca di un compratore per la loro preziosa merce clandestina. Gli uomini sono predatori di tombe. La merce che trasportano è il cadavere di un ragazzo italiano. Il compratore dovrebbe essere una clinica medica universitaria. Vendere defunti agli anatomo-patologi, che li sezionano per fare lezione agli studenti o per condurre esperimenti, è una pratica assai diffusa, tollerata dalle autorità del Regno Unito. I medici non fanno troppe domande sulla provenienza dei corpi. E i predatori fanno fortuna: un cadavere in buone condizioni vale dieci guinee, l’equivalente di una decina di sterline odierne (quattordici euro), trenta volte la paga che il dodicenne Charles Dickens guadagnava in una settimana in fabbrica, nel 1824, prima di diventare uno scrittore.

‘Il commercio di cadaveri è dunque una professione redditizia. Ma non stavolta. I sanitari del King’s College, la facoltà di medicina sullo Strand, notano che il corpo è quasi caldo e che la causa del decesso è un violento colpo al cranio. Insospettiti, trattengono gli sciacalli con una scusa e chiamano Scotland Yard. I tre sono arrestati, incriminati per omicidio, condannati a morte: vengono impiccati un mese più tardi, davanti a una folla di quarantamila persone, e i loro corpi, con macabro sarcasmo, finiscono al Royal College of Surgeons, affinché i suoi chirurghi si esercitino a piacimento. La vicenda cattura l' attenzione di tutto il Paese.

‘Il Times dedica pagine alle indagini. L’opinione pubblica si commuove a conoscere i particolari della vittima: "The Italian Boy", il ragazzo italiano, come lo hanno soprannominato i giornali, un piccolo mendicante che faceva spettacolini di strada attorno al mercato di Covent Garden, con appesa al collo una gabbietta in cui corrono due topolini bianchi. Ma perché sia fatta piena luce sulla sua identità, e sul significato della sua fine, devono trascorrere due secoli.

‘Bisogna arrivare ai giorni nostri, alla ricostruzione di un' ostinata cronista inglese, Sarah Wise, il cui libro, "The Italian boy, murder and grave robbery in 1830s London" (Il ragazzo italiano, omicidio e furti nelle tombe nella Londra del 1830), sostiene che la morte del piccolo italiano segnò il trapasso tra due epoche: preannunciando l’avvento dell' era vittoriana, a base di ordine, efficienza e moralità. Il ragazzo si chiama Carlo Ferrari e viene dal Piemonte, precisamente dalla Savoia, dove un padre con troppe bocche da sfamare lo vende a un avventuriero di passaggio. Questi lo porta con sé oltre la Manica, a Birmingham, rivendendolo a un "padrone" di giovanissimi senza tetto e senza famiglia, tenuti sostanzialmente in schiavitù, obbligati a chiedere l' elemosina o esibirsi nelle strade. Carlo passa da un padrone all' altro, scappa, viene ripreso, picchiato, venduto di nuovo. Fugge ancora, a Londra, dove si arrangia a sopravvivere da solo, con una gabbia di topolini bianchi e una tortora ammaestrata. Nel 1831, ha quattordici anni: bassa statura, occhi grigio-chiari, capelli lunghi e lisci, lineamenti dolci. A Oxford street, a Covent Garden, nei vicoli maleodoranti dell’East End, è una presenza familiare a bottegai, passanti, poliziotti, con il suo grido mezzo in francese, mezzo in italiano, «Donnez un louis, signor», donatemi un luigi.

‘Nelle strade di Londra, in quegli anni, gli "Italian Boys" sono numerosi e ben riconoscibili. Ci sono i "figurinai", che lavorano la cera, fabbricando statuine, accompagnati da fratelli maggiori o genitori, molti provenienti da Lucca; i burattinai, con un teatrino ambulante di fantoccini e marionette; e all' ultimo gradino i menestrelli, giocolieri, ballerini, che si esibiscono insieme a piccoli animali ammaestrati. Carlo Ferrari (chiamato anche Carlo Feriere e Charles Ferrier, alla francese, nei documenti giudiziari), è uno di questi ultimi. Ogni tanto va a rifugiarsi nella Cappella Italiana di Oxenden street, all’incrocio con Haymarket, dove gli offrono un tozzo di pane e un pavimento asciutto su cui dormire. Ma la sera del 4 novembre è in un’altra zona dell’East End, a Crabtree Row. Fa freddo, piove, le case scompaiono nella nebbia; lui ha fame e non sa dove dormire. Il destino lo porta ad accucciarsi sotto la tettoia di una stamberga: l’abitazione di John Bishop, il capo di una banda di commercianti di cadaveri. Nel buio, un vicino sente un grido e un tonfo. Poco dopo, i tre assassini caricano la merce sul carro, dirigendosi verso il centro. Fanno tappa in un pub per scaldarsi con gin e rum, s’attardano con una prostituta, bussano alla porta di un ospedale, poi al King’s College. Il giorno seguente, quando la polizia perquisisce la baracca di Bishop, i suoi bambini stanno giocando con la gabbia di topolini del mendicante italiano.

‘Non è la prima volta che gli sciacalli di cimiteri, non trovando corpi sottoterra, ne procurano di freschi, uccidendoli con le loro mani: a Edimburgo, tre anni prima, due predatori di tombe sono stati incriminati per l' omicidio di tredici vagabondi. E a Londra spariscono di continuo ragazzini, per lo più orfanelli, mendicanti o delinquenti, spesso italiani: quando la polizia annuncia il ritrovamento del corpo di Carlo Ferrari, otto famiglie di immigrati vanno all' obitorio per vedere se è il loro bambino. Da morto, Carlo diventa una celebrità. La sua storia viene rappresentata a teatro. La buona società, inorridita da tanta miseria e depravazione, fa autocritica: così non si può andare avanti.

‘Negli anni successivi, il parlamento approva una legge per regolamentare il modo con cui le cliniche mediche si procurano cadaveri per i loro studi scientifici. Una storia alla Oliver Twist, ma autentica e senza il lieto fine del romanzo di Dickens. Perfetta per rivedere l’Inghilterra dell’Ottocento. E per immaginarci dentro i nostri primi immigrati: la prossima volta che passate da Covent Garden, chiudete gli occhi e provate a sentire la vocetta di Carlo Ferrari, che squilla «donatemi un luigi, signor». Così eravamo, a Londra, poco meno di due secoli fa.’

21/11/14 The Ratcliffe Highway Murders

Sad but true, one of my smuggest historico-moments was finding the apparently lost grave of the Marr family in the graveyard of St George’s in the East; they were among the victims of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders of 1811.

I took this pic and will let David Bingham, on his wonderful The London Dead website, tell the rest of the story here:

http://thelondondead.blogspot.co.uk/2014/06/the-ratcliffe-highway-murders-1-marr.html

And, one of my favourite true crime books (it makes my top 3 in fact) is The Maul and the Pear Tree, co-authored by PD James and TA Critchley (1971, reissued 2010), providing a fantastic ‘solution’ to the mystery.

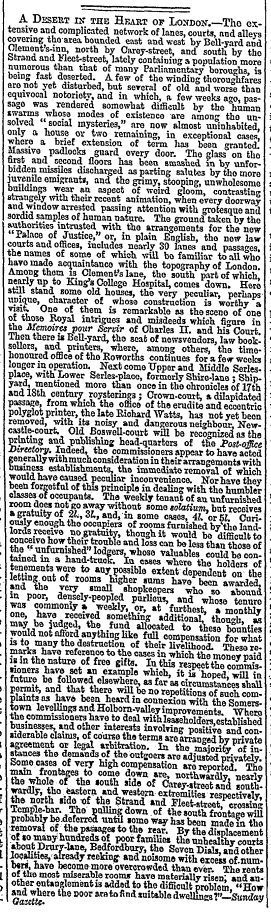

9/10/14 The death of Bell Yard

One of my favourite Victorian cuttings: on the imminent demolition of the area north of the Strand near Carey Street (Sweeney Todd territory), for the building of the Royal Courts of Justice. It was reprinted in The Times of 12 November 1866, from the Sunday Gazette. For more, see the entry below at 20/4/13.

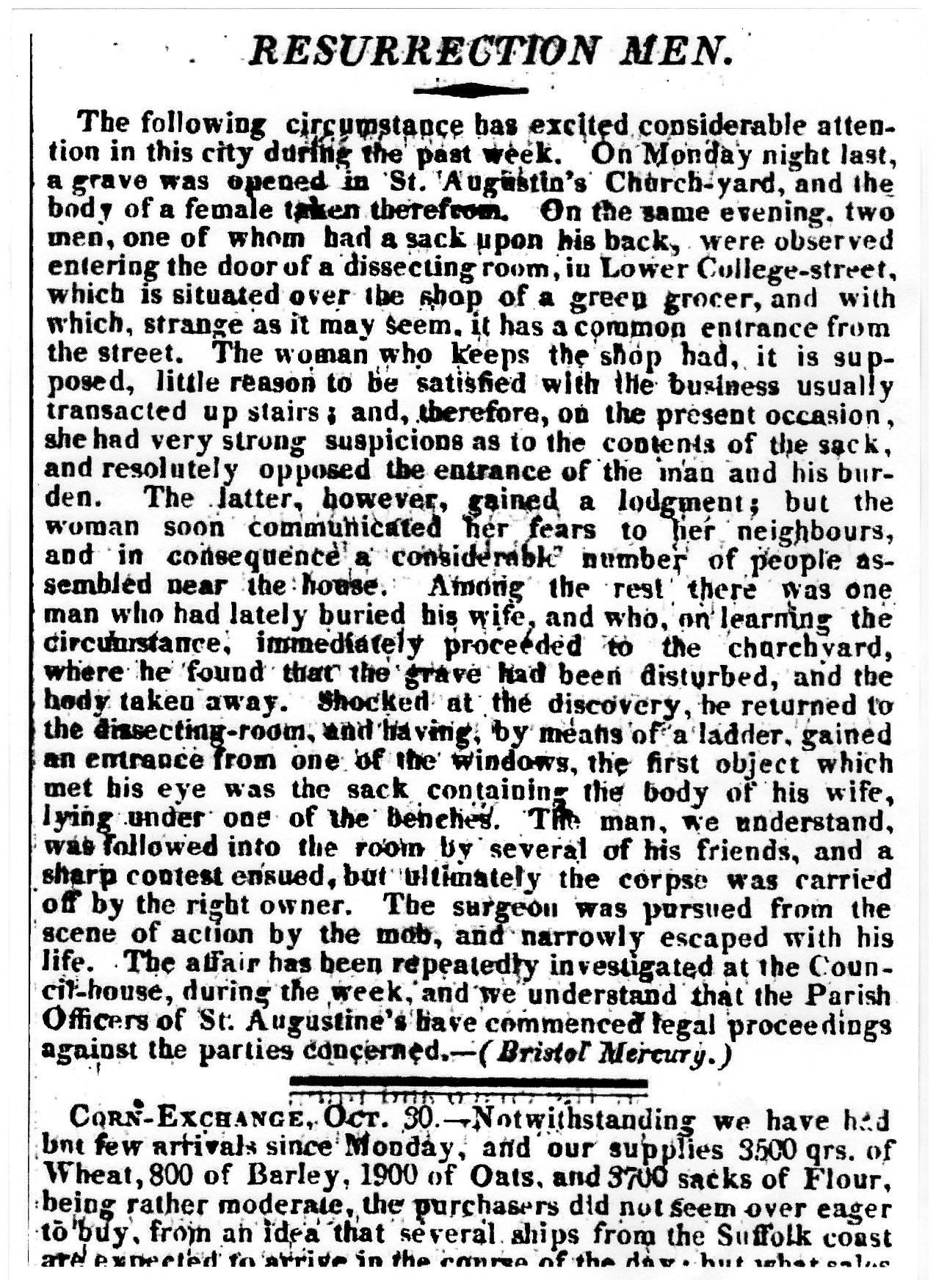

30/9/14 A dissecting-room over a greengrocer’s shop...

Really not a great idea, as this horrendous story of 1822 shows. Source: Berrow’s Worcester Journal, 7 November 1822.

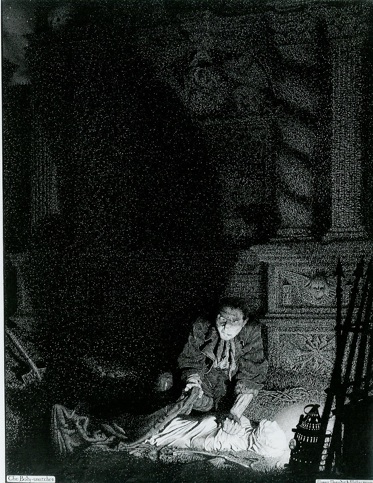

29/8/14 My favourite picture of a bodysnatcher is . . .

It’s called The Bodysnatcher (would you believe it?), and what is fascinating is that it was drawn in 1913, more than 80 years after the end of bodysnatching.

The artist is Morris Meredith Williams, and the very generous David Patterson, Collections Manager at the Edinburgh City Art Centre, has allowed me to post it here (would that all archives were as generous with out- of-copyright material). Please, if any of you want to download it, do give credit where it’s due: ‘City of Edinburgh Museums and Galleries’.

What Meredith Williams has captured better than any other artist is the smirking furtiveness of Resurrection Men; and the sense of violation and the vulnerability of the recently departed human being -- this scene has echoes of a sexual assault.

The act is taking place in a rather fancy-looking vaulted area, and top left, the stars are twinkling down on the goings-on. In the foreground is his ‘dark lanthorn’, which threw the rays downwards to avoid drawing attention.

The artist may well have read about the Italian Boy case as this villain has a look of John Bishop, murderer, about him, and those hideously powerful forearms match exactly the 1831 descriptions of Bishop.

However, he may also have come across this article in Dickens’s magazine All the Year Round (dated 16 March 1867), written by a reporter who recalled the day in 1828 that he happened to be in the corridors of parliament when the Select Committee on Anatomy was taking evidence; among the witnesses were a number of Resurrection Men. The reporter (and it is possible that it was a young Dickens himself) remembered: ‘For several days in the summer of 1828, a certain committee room of the House of Commons, as well as all the passages leading to it, were thronged by some of the vilest beings that have perhaps ever visited such respectable places. Sallow, cadaverous, gaunt men, dressed in greasy moleskin or rusty black, and wearing wisps of dirty white handkerchiefs round their wizen necks. They had the air of wicked sextons, or thievish gravediggers. There was a suspicion of degraded clergymen about them, mingled with a dash of Whitechapel costermonger. Their ghoulish faces were rendered horrible by smirks of self-satisfied cunning, and their eyes squinted with sidelong suspicion, fear and distrust.’ To me, that is a verbal portrait of the creature Morris Meredith Williams depicted in 1913.

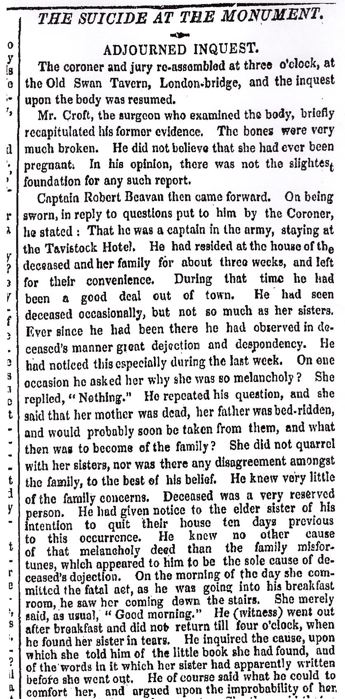

10/8/14 Two News Stories That Made Boz Feels Homesick

In mid-September 1839 the newspapers were running two London stories that inflamed the imagination of Charles Dickens: but he was away from London at the time, and the flavour of these tales gave him a pang of homesickness.

On 18 September he wrote to his friend John Forster: ‘What a strange thing it is that all sorts of fine things happen in London when I’m away! I almost blame myself for the death of that poor girl who leaped off the Monument – she would never have done it if I had been in town; neither would the two men have found the skeleton in the sewers. If it had been a female skeleton, I should have written to the coroner and stated my conviction that it must be Mrs [Jack] Sheppard [notorious villain]. A famous subject for illustration by George [Cruikshank] – Jonathan Wild forcing Mrs Sheppard down the grown-up seat of a gloomy privy, and Blueskin, or any such second robber, cramming a child (anybody’s child) down the little hole, Mr Wood [alderman] looking on in horror, and two other spectators, one with a fiendish smile and the other with a torch, aiding and abetting.’

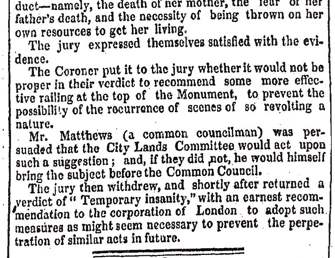

Below are the two stories in the Morning Chronicle of 14 September 1839, the first on the suicide of 22-year-old Margaret Moyes, a baker’s daughter, who jumped from the Monument on 11 September; the second on a skeleton found sitting upright in a sewer beneath the Strand.

At the bottom, the Era and the Examiner conclude the tales.

Source for the letter to Forster: The Letters of Charles Dickens, The Pilgrim Edition, edited by Madeline House and Graham Storey, Volume 1, 1820-1839 (1965), p582.

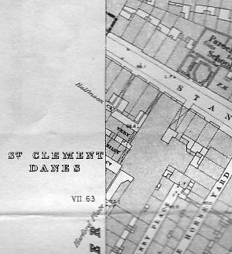

For a map showing Shire Lane/St Clement Danes, see post below dated 20/4/13.

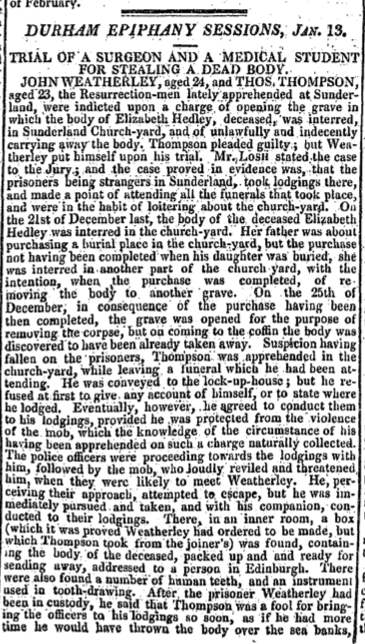

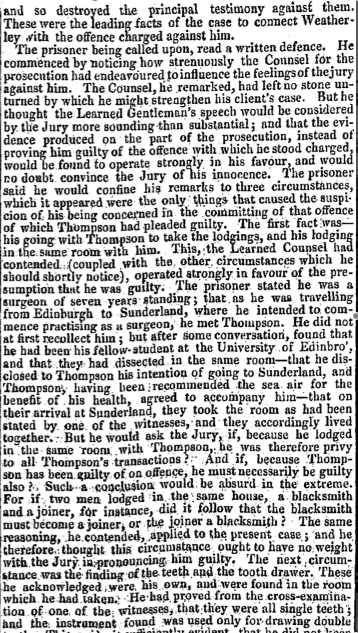

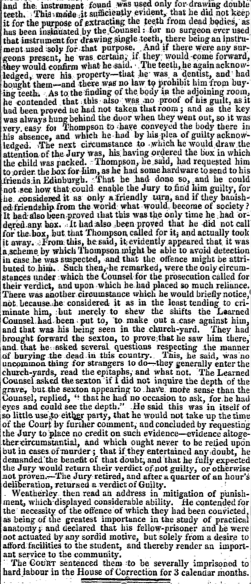

22/7/14 Stealing Elizabeth Hedley

By the 1820s, it was uncommon for a surgeon to be arrested and prosecuted for doing his own bodysnatching – usually only the hired hands, the resurrectionists, got caught and did time in gaol. But this Sunderland story, from the Morning Chronicle of 21 January 1824, shows that surgeons still did their own digging sometimes.

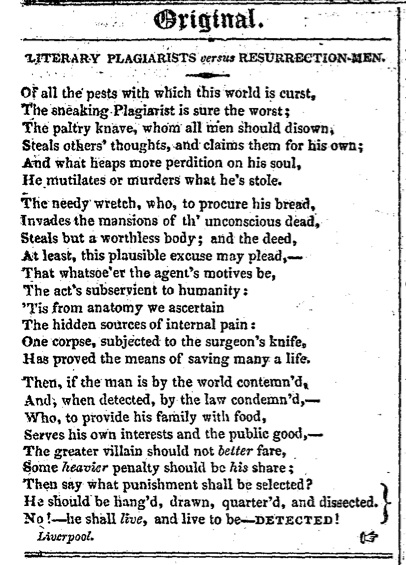

11/7/14 Why is a plagiarist just like a bodysnatcher?

Let the Liverpool Mercury of 20 May 1825 explain, in verse.

26/5/14 Nova Scotia Gardens, part 4

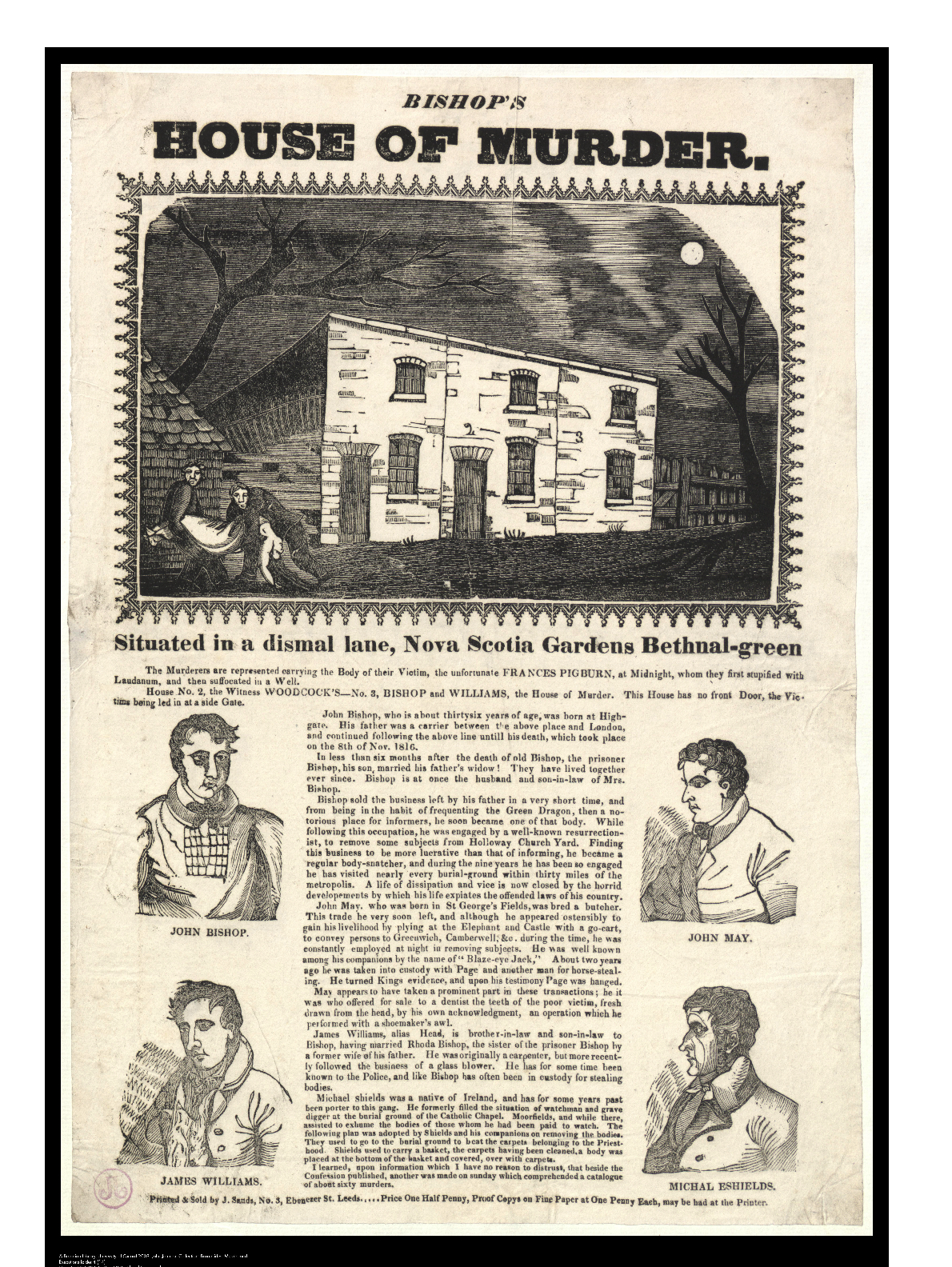

Yet another depiction of Nos 2 & 3 Nova Scotia Gardens, this time, from a cheap broadsheet published during the murder trial in 1831. The mug-shots have been re-used from a previous production and are nothing like the villains in reality; and the names are wrong in two of the captions – all par for the course at the bargain-bin end of journalism of the era. . .

10/4/14 Nova Scotia Gardens, part 3

Tracy Williams came along to a talk I gave a fortnight ago and afterwards told me that she had ancestors who had lived in Nova Scotia Gardens, the site of the Italian Boy killings. She wrote out the following for me – the results of her labours in the census, births, marriages and deaths indexes.

(For more on The Gardens, see also the stories below at 18/1/14 and 22/11/13.)

‘John and Euphan Gullen probably moved to London from Edinburgh some time in the 1760s. He was a paper-maker and she was the daughter of a shipmaster, so they may have had a little money. By 1841 their grandson (my great-great-grandfather), John Hart Gullen, was a humble willow-cutter living in the slums of Bethnal Green. His daughter, Emma, was born at 5 Nova Scotia Gardens in 1843 [the killers had lived at Nos 2 and 3, twelve years earlier]. The family must have left the cottages by 1849 because Emma’s mother, Elizabeth, died of cholera in that year at 1 Virginia Row, nearby.

‘In 1882 John Hart Gullen died of tuberculosis at the age of 64 in Bethnal Green workhouse. A number of his children lived to adulthood, and one of them was my great grandfather, James Gullen. He found a good trade as a marble mason and moved to Hoxton, then Edmonton, where a few of his descendants are still living. At the first chance I had to talk to my mum and her sisters about the Gullens and the notoriety of Nova Scotia Gardens, my Aunt Jean said something that has stayed with me: “I’m proud of them because they survived.” ’

23/3/14 Anti-Resurrection gates at Bunhill Fields

Bunhill Fields burial ground in the City Road (near the Old Street roundabout) is one of the best-preserved in London – a beautiful park with the graves and memorials of London religious Non-Conformists, including William Blake, John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe.

The graveyard had been particularly well-protected against the menace of the bodysnatchers: while the smaller parish and private grounds all around the St Luke’s and City Road area had been repeatedly ransacked in the quest for anatomical specimens, Bunhill took security very seriously. This spiked gate stood at the western edge of the graveyard for decades, and for long after the resurrection men had been sent into early retirement by the 1832 Anatomy Act.

The photographs below date from the Edwardian era, and show the eastern, City Road entrance to the burial ground – not so very different from how it looks today.

19/3/14 Urine Town: Whither Can You Widdle?

London at the time of the Italian Boy killings was awash with all manner of unmentionable filth. A letter was received by The Lancet in April 1831 from an angry septuagenarian who lived in the countryside. He was no longer very fast on his feet, he wrote; and whenever he came up to London for the day and was caught short, all he could see were fierce notices stating ‘Commit No Nuisance’ (that’s a euphemism for ‘do not urinate’). If he ever decided to chance it, and attempt a discreet pee, ‘he was furiously driven off by the new [Metropolitan] policemen.’

Lancet, 16 April 1831

17/3/14 Corpsing on stage

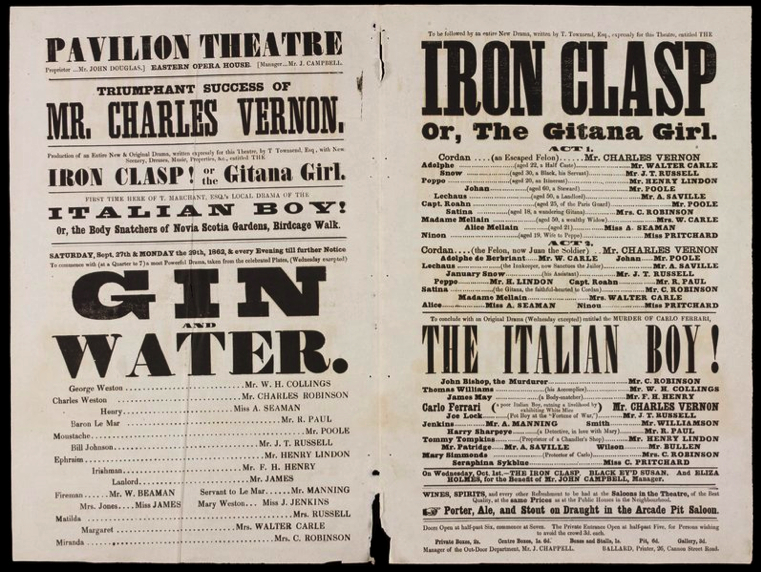

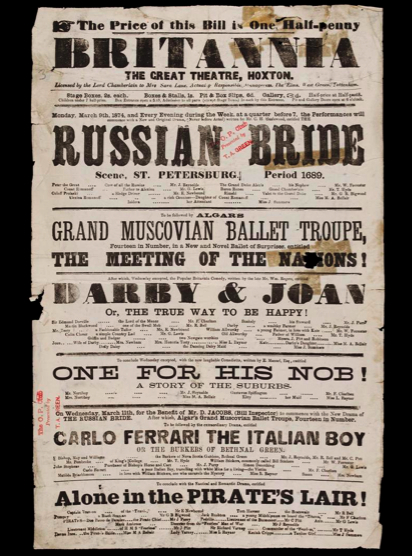

The murder of Carlo Ferrari spawned a number of plays – he arose out of his grave for performances throughout the 19th century. The Pavilion Theatre was in Whitechapel, and this playbill dates to September 1862. Below that, the Britannia Hoxton playbill is from March 1874. One For His Nob! refers to a blow to the head, as experienced by the play’s hero in Act II. In case you were wondering.

.

18/1/14 Nova Scotia Gardens – and what grew there. Part 2

Disgusted by what had become of the site of John Bishop’s murder house (see Part 1 posted on 22/11/13, below) banking heiress Baroness Burdett Coutts decided, in 1852, to buy the land and construct a market building (below left) and tenements for the poor (below right) on Columbia Road. Her architect was Henry Darbishire, also responsible for Holly Lodge Estate in Highgate (Holly Lodge locals will spot the similarity between Columbia Market and the Estate).

In an amazing act of vandalism, both Columbia Market and the Columbia Square dwellings were demolished in the late 1950s/early 1960s, despite being structurally sound. The pictures below show the market and the street running behind it in their final days. The aerial shot beneath them shows the cleared site, with the blocks of the Dorset Estate council housing newly completed. (Hackney Road is running immediately to the north of these.) The picture at the bottom is of the Berthold Lubetkin-designed tower block Sivill House, which is just south of the Dorset Estate blocks.

Photographs, top row: the Columbia Market and Columbia Square pictures are part of a collection held at the London Metropolitan Archives, with the shelfmark 72.COL;

LMA, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1, tel: 020 7332 3820

www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/london-metropolitan-archives/visitor-information/Pages/default.aspx

Second row: from The East End Then & Now, edited by Winston G. Ramsey, published by After the Battle.

Aerial shot: Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archive collection; THLHL&A, 277 Bancroft Road, E1 4DQ, tel: 020 7364 1290. localhistory@towerhamlets.gov.uk Sivill House: photographed in summer 2013 by the web mistress/blogger.

8/12/13 Behind Closed Doors: one view of how people felt about dissection in the 1820s

By the time of the Italian Boy killings, the secretive nature of anatomists and goings-on in dissection rooms was being widely criticised. Public opinion towards science would be improved, many said, if doctors would only be more open and honest about what went on during dissection, and about what became of the remains of the anatomised subject.

In 1829, illustrious surgeon

George Guthrie wrote an open letter to the Home Secretary, trying to put the record straight on various aspects of the subject. Guthrie believed that his years of experience had given him access to the powerful emotions, and sometimes lack of them, aroused by permitting a body to be opened up for medical teaching. In a letter that challenges many of the commonly held notions of the day, he claimed that the poor were, in fact, nothing like as squeamish about having their bodies anatomised (and possibly bottled up in a medical museum) as was generally believed. Guthrie also challenged the comforting myth that dissected remains ever finally received a Christian burial.

Guthrie wrote: ‘Few individuals really care much what becomes of their bodies after they are dead; they wish to be buried, or disposed of, according to the custom of their country. It is the last sad duty of their friends to attend their remains, and it is considered either as a want of regard or of respect for the dead, when it is not done in the usual manner. When a person is dissected, without Christian burial, or exhumated afterwards, it is the feelings of the surviving friends which are injured; it is their rights that are outraged, and they resent it accordingly. Many individuals, and medical men in particular, would devote their bodies to dissection if it were not that they do not wish to distress those whom they leave behind.

‘When permission is given to open a body, it is often accompanied with the express condition that no part whatever shall be taken away in order to be preserved in the museum of the anatomist. It is the feeling which dictates this request that operates against the complete dissection of a body. If a relative or friend submits to have the body of his relation or friend examined – as a debt due to mankind and in order to facilitate the means of obtaining information, by which the sufferings of others may be mitigated or removed – he sacrifices his feelings only for a moment; but if he were to yield a beloved mother, wife, or sister, for complete dissection, he has, in the first place, to conquer the feeling of the indelicacy of the proceeding; and, secondly, the horror of afterwards hearing that various parts of the person he most esteemed and loved are exposed in bottles, and the gaze of the curious.

‘It has been proved that where dissecting establishments have been attached to hospitals, they have not had the slightest influence in diminishing the number of applications for admission; although it is the common opinion of the poor that all who die without friends are regularly dissected in them. They place no reliance on the form of burial they see going on; they do not believe the body is actually buried in the coffin, which goes to the churchyard; still they are not deterred from seeking admission into hospitals; they care very little about the matter.

‘To one patient I said, half in jest, “I certainly will have a skeleton made of you, if you die, that you also may be of use to others.” His reply was, “If you do not, I dare say somebody else will, and I had rather you than anybody.” He said this laughing loudly, in which he was accompanied by every other patient in the ward. If he were to die, it would be a matter of perfect indifference what became of him.’

There was nothing secretive about anatomy nor the places where it was practised, Guthrie continued: ‘The doors of every dissecting room in London are always open, there is nobody to watch them, they swing backwards and forwards on a pulley and weight, that they may shut of themselves in case anybody leaves them open; every man may walk in and walk out whenever he pleases; many persons do, but no one gives himself any concern about what is going on. The neighbours care nothing about it, and unless, from some accident, the place becomes offensive, no one interferes; although the resurrection men, for their own purposes, sometimes endeavour to excite a little commotion.

‘In fact, the public care nothing about it, and the dissection of dead bodies requires only the support of the law, and proper regulations, to become as accessible a study in London as in any other part of Europe.

‘It is not to the bodies of persons who are hanged that dissection should be confined; all persons who die under sentence for criminal offences should be given up for dissection. . . Few of those who die in the hulks or on the criminal side of gaols have friends who care what becomes of them, either alive or dead.

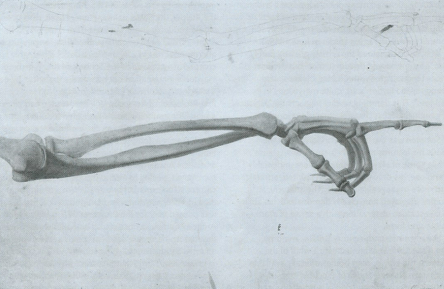

‘It has been gravely stated, and some faith has been given to the assertion, that, after dissection, the remains of a body may be still buried with religious rites and ceremonies. Some converts to dissection have, perhaps, been gained by this statement than which nothing can be more unfounded; for few of the bodies given up for dissection either can, or ought, to be afterwards committed to the ground. I have no hesitation in saying that few ever will be buried. . . It is the separation of each part in very small portions which establishes in the mind’s eye an intimate acquaintance with the whole structure. . . The soft parts being thus treated, what should be done with the bones? They ought to be in the possession of the surgeon, articulated or made into a skeleton.

‘The remains of non-criminals may be buried but it should be done privately, and without ceremony; those religious rites, which it is no less our duty than our inclination to afford, having been performed previously to the dissection taking place.

‘Thirty years ago, none wished to look at the body of a murderer; now, the desire for knowledge induces many to overcome their prejudices and not only to look at a dead body, but to hunt it out in a dissecting room; and examine all the bumps on the head, and compare the resemblance with the penny woodcuts placed at the head of the dying speech and confession. . . The very fact that the increased desire for knowledge has brought indifferent persons into a dissecting room in such numbers as to make their presence troublesome shows that prejudices upon this point are fast subsiding.’

A Letter to the Right Honourable the Secretary of State for the

Home Department on the Report of the Select Committee on Anatomy (1829)

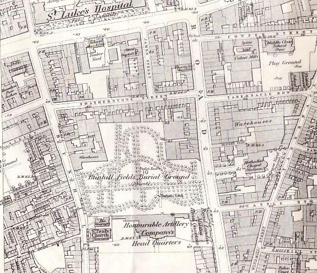

22/11/13 Nova Scotia Gardens – and what grew there. . .

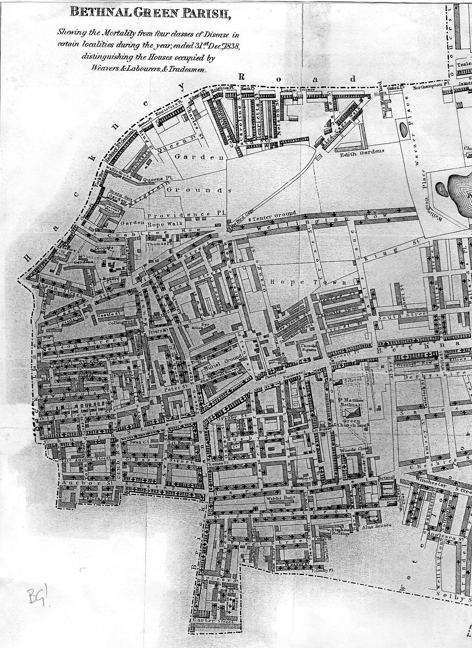

The Italian Boy murders took place in a tiny district called Nova Scotia Gardens, though that name never actually appeared on any map. The 1838 parish map below only marks it as ‘Garden Grounds’ – just north of Crabree Row, today’s Columbia Road.

After the killings, Nova Scotia Gardens took on several new unofficial names: Burkers’ Hollow; the Hackney Road Hollow; The Ruins. (False) stories grew up that beneath was a secret system of tunnels and cellar rooms.

A journalist writing in the late 1880s recalled: ‘In Bethnal Green, the hideous event produced a deep sense of horror that years have not altogether removed. The district of the crime was looked upon for a long time with repugnance and apprehension, and many are now the ageing inhabitants of the districts who can well recall the thrill of horror that shot through them when they found themselves out on dark evenings in the neighbourhood overshadowed by the memory of this hideous and inhuman outrage.’ (Eastern Argus, 9 April 1887.)

Another article, from the end of the century, was written by an aged resident of Shoreditch, who recalled, ‘Just past Cooper’s Gardens, there used to be a row of dilapidated old houses standing back from the line of frontage and in a hollow, with a strip of waste land in front, on which was laid out for sale flowers, greengrocery and old rubbish of all kinds; but. . . the large-hearted philanthropist, the Baroness Burdett Coutts, purchased them and the whole of those fearful hovels called Nova Scotia Gardens, once so famous in the days of Burking.’ (Hackney Express & Shoreditch Observer, 1 January 1898, ‘Chapters of Old Shoreditch from an “Old Shoreditch Observer” ’.)

The baroness bought up the land and property and demolished, but rebuilding was delayed, and so the area degenerated even further. The illustration below appeared in George Godwin’s 1859 campaigning book Town Swamps and Social Bridges, and shows ‘the table mountain of manure’ (as another sanitary investigator put it) that built up during the delay in redevelopment. The drawing shows children playing on the heap of sewage and refuse, which Godwin saw on his visit. (It’s all a bit Terry Gilliam. . .)

Below, from the top: George Godwin’s 1859 sketch of the manure mountain; sightseers touring the site of the killings at No 3, Nova Scotia Gardens,, in autumn 1831; the 1838 parish map of Bethnal Green, drawn up to show disease and poor sanitation – showing ‘Garden Grounds’ near the top.

16/10/13 The isles of London

The capital always had plenty of ‘islands’ ’ chunks of built territory that had a sense of being cut off from close neighbours. Wapping Island and Bermondsey’s Jacob’s Island were at least separated off by ditches and inlets. But there was no such topographical feature at ‘Piggy’s Island’ – a 19th-century name for Goldsmith’s Square, halfway along Goldsmith’s Row, off the Hackney Road.‘ Jews’ Island’ was a not-complimentary gentile term for a run of dwellings in Bethnal Green, at Teesdale Street and Blythe Street, built by Jewish developer Woolf Davis and inhabited by Jewish residents.

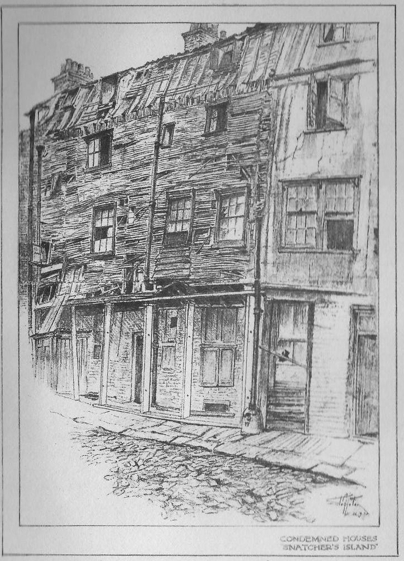

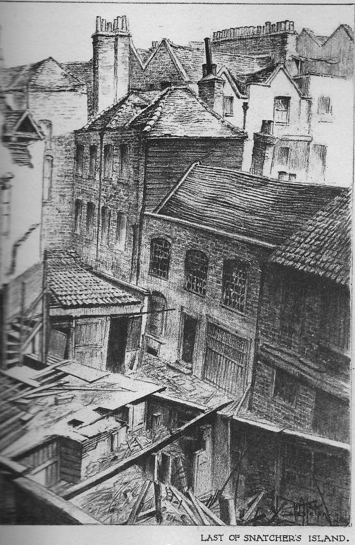

‘Snatcher’s Island’ stood at the junction of Wild Street and Great Queen Street in Covent Garden, on the north-eastern corner. Its formal name was Strickland’s Yard but it was called Snatcher’s Island because of the belief that it had more than its average quotient of bag-snatchers, snotter-haulers and other tea-leafs in residence. Sadly, it had nothing to do with bodysnatchers, despite the several graveyards in the vicinity. (Opposite and to the south was a tiny court, whose nickname, Very Silly Court, made it into the Ordnance Survey map of 1874, see below – it’s just heading off the left-hand side of the map.)

The pictures below show Snatcher’s Island just before demolition, sketched from a vantage point on the roof of the Lambert & Butler factory in Drury Lane/Wild Street. They appear in the 1924 book London Alleys, Byways and Courts, written by Alan Stapleton and illustrated by his drawings.

27/9/13 Great fogs of pre-Victorian London – they were tasty and colourful

Yes, it’s a cliche, but fogs really did used to make London more mysterious and eerie – people even said so at the time. I came upon these two passages while researching The Italian Boy – they’re from 1826 and 1837 respectively.

Firstly, here’s Peter George Patmore, in The Mirror of the Months, writing about autumn and winter fogs:

‘Now the atmosphere of London begins to thicken overhead, and assume its natural appearance – preparatory to its becoming, about Christmas time, that “palpable obscure”, which is one of its proudest boasts. . . As an affair of mere

breath, there is something tangible in a London Fog. . . In a well-mixed Metropolitan Fog there is

something substantial, and satisfying. You can feel what you breathe, and see it too. It is like breathing water, as we may fancy the fishes to do. And then the taste of it, when dashed with a due seasoning of sea-coal smoke, is far from insipid. It is also meat and drink at the same time; something between egg-flip and omelette soufflée, but much more digestible than either. Not that I would recommend it medicinally, especially to persons of queasy stomachs, delicate nerves, and afflicted with bile. But for persons of a good robust habit of body . . . there is nothing better in its way.’

In the 19th century, Punch magazine found fog an ongoing source of visual wisecracks. Below left: a little urchin leaps out of the fog and scares an old lady. Below right: is it time to re-introduce the 18th-century ‘link man’ to London, to guide people on their way home? Bottom: the various uses to which patented anti-fog glass could be put.

My second foggy (and smoky) extract is from Dr John Hogg’s fantastic compendium of facts plus eccentric opinion – London As It Is (worth checking out in its entirety):

‘The cross on St Paul’s Cathedral is nearly on a level with Hampstead Heath, and the clearness of the atmosphere at that height may be easily seen in London by observing that, although the town may be enveloped in fog and smoke, the gilt ball and cross on the cathedral are sparkling in the sunshine. The same contrast is vexatiously experienced if a person mount the dome of the building for the purpose of seeing the metropolis at one view; on reaching the elevated station, he sees the country for many miles around, but if he looks for London, he finds himself literally in nubibus, a firmament being between him and it . .

‘London is frequently enveloped in a mist, or fog, of greater density than is observable in any other part of the kingdom, more particularly in winter. . . The dry fog, so frequently observed in the months of November and December in London, seems to be composed chiefly of smoke, which, from its great weight, is unable to rise from the earth, when the surrounding atmosphere, as indicated by the fall of the barometer, becomes specifically light. The colour of it corresponds with that of smoke, and it generally possesses a sooty, suffocating odour. Its sudden invasion of, and as sudden departure from, different parts of the town, and its not being seen often after midnight, or at any other time when fires are not generally burning, would lead one to conclude that exhalations from the earth have very little to do with this species of fog. It is of a bottle-green colour, but if the barometer rise, it will either totally disappear, or change into a white mist.

‘It is sometimes so dense as to prevent objects being discerned even at the distance of a few yards, and, in consequence, many accidents occur in the streets, from the carriages and other vehicles coming into contact with each other. This state of atmosphere is considered peculiar, and has the appellation of “the London fog”. It causes such darkness that lights are indispensable for the transaction of business. It sensibly affects the organs of respiration, so much so, indeed, that persons having delicate lungs frequently experience a feeling of suffocation. Powerful as is the gas flame in the lamps, the light is not discernible many yards from the lamp-post. . .

‘The principal cause of complaint against gas works, soap-, sugar- and candle manufactories, breweries, distilleries and foundries is the frequent vomiting forth of dense volumes of black, suffocating smoke, filling all the adjoining streets with stifling fumes and darkening the very atmosphere. The effluvia occasioned by the former of these works is well known as being injurious to health, and it is unfortunate for the inhabitants that establishments of this description are not kept at a proper distance from their habitation. The contamination of the atmosphere by repeated inhalations of nearly two millions of persons cannot easily be avoided, neither can the half a million of fires in private houses be suppresesd; but the wholesale poisoning of the air by these works might be prevented, without any public incovenience being occasioned. In a word, all public works should consume their own smoke, or be prohibited in the metropolis.

‘Many persons think that the smoke is beneficial rather than prejudicial to health in London, on the idea, probably, that it covers all other offensive fumes and odours; this notion cannot be founded in truth; for even admitting that it conceals from the senses innumerable effluvia that would otherwise have caused disgust, it is in itself most prejudicial to animal, as well as to vegetable, life. It need only be remarked that smoky places are invariably the dirtiest and the most unhealthy, whence it is easy to discover the true bearing of the facts of the case.. . Moreover, smoke is prejudicial in another way: light is essential to vigorous health in both the animal and the vegetable economy, but the enlivening rays are effectually excluded in London, for days together, by the volumes of thick smoke which hang over the town.’

3/9/13 Italian Boys in photographs and in stone

Itinerant Italian boys sold plaster figurines and displayed small animals in city streets well into the 20th century.

Below are photographs of (from the left) an Italian boy in London with a monkey, photographed in 1854; figurine and trinket vendors photographed in the 1870s; an Italian boy in the early 20th century.

Above is a sculpture of a figurine seller in Tuscany – commemorating the emigrants of the city of Lucca and its surrounding towns in the nineteenth century. The statue stands in the courtyard of the Museum of Plaster Figurines and Emigration, at Palazzo Vanni in the small town of Coreglia Antelminelli, not far from Lucca. The museum celebrates the art of the figurinaii – the plaster artists who manufactured the statuettes sold by the street vendors. It has over 1,000 figurines on display and tells the story of how the figurinaii travelled all over Europe, America and to the Far East.

The museum’s website:

http://www.luccaterre.it/en/dettaglio/2866/Museo-della-Figurina-di-Gesso-e-dell-Emigrazione.html

19/8/13 The Workhouse is under threat, again

The body of the Italian Boy, Carlo Ferrari, was buried in 1831 in the graveyard of the St Paul’s Covent Garden/Strand Union workhouse in Cleveland Street, London W1 (above). The graveyard was closed in 1853 and afterwards cleared, and Carlo may have ended up in Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, or he may still be down there somewhere – the fate of these bodies has never been fully resolved.

Recently, a number of campaigners in my local area succeeded in saving the 18th-century workhouse building from demolition; in fact, it is now Grade II listed. I wrote the letter below back in 2008, and I still feel exactly the same way, as I learn that the later, unlisted, Victorian wings are now under threat of demolition.

Part of the Victorian section of the workhouse, which is now under threat of demolition; the Windeyer Institute,

on

the right, was being demolished when I took these pictures a few months ago. More detailed shots can be viewed at

Peter

Higginbotham’s website www.workhouses.org.uk/Strand/

The Victorian buildings are not considered significant, historically, by the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, which is pressuring Camden Council to permit demolition.

It’s very odd that an arm of the National Health Service has morphed into a money-grubbing, heritage- destroying property developer – presumably not quite what Nye Bevan had in mind back in 1948. Any new residential units will be marketed directly to investors in the Far East, just as has happened with the hideous block that is being erected on the site of the Middlesex Hospital in Goodge Street.

If, like me, you believe that the Victorian extensions are well worth saving, and would convert well into housing units in their own right, please join our Save the Workhouse campaign, whose website is at http://clevelandstreetworkhouse.org

On a more general note, Griff Rhys Jones wrote brilliantly here http://news.fitzrovia.org.uk/2012/07/24/ fight-this-undemocratic-attempt-to-manipulate-fitzrovia-into-something-it-is-not/ about the interminable battles we face in our area against the dark forces intent on buggering up our lovely, shabby, lively, quirky little corner of London.

7/7/13 St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch – pinhole camera shot

Pete Locker, who lives on the Boundary Street Estate, close to St Leonard’s, took this night-time shot of the church using a pinhole camera. I think it certainly captures the aura of this creepy place of worship – which is every bit as unsettling as the Hawksmoor churches highlighted by Peter Ackroyd in his 1985 novel Hawsksmoor.

You might know St Leonard’s as St Saviour’s-in-the-Marsh – in the BBC sitcom Rev. It was where my two murderers in The Italian Boy, John Bishop and Thomas Williams, married their wives; and in 1825 James May, resurrectionist and co-accused with Bishop and Williams, was caught in the act of dragging a body from the grave in the burial ground of the church.

Despite plenty of locals as eyewitnesses to the crime, and a ludicrous defence on the part of May, the magistrate acquitted May. Resurrection men often got the benefit of the doubt in such cases, as the judiciary were only too aware that an unhappy bodysnatcher might start to reveal the names of the surgeons and hospitals he was supplying. Better, in many cases, to ‘keep them sweet’ with an acquittal or a light sentence. .

© Picture: Pete Locker

6/6/13 Mysterious bones – from The Times, 23 November 1848

‘SUPPOSED MURDERS’

‘On Saturday night, a person named Price, residing in Bethnal Green,

was digging in his garden when he turned up a human skull, and on

making further search exhumed an entire skeleton, which, however, on

being examined by a medical man, was found to have a rib too many. This occasioned a further search, and a second skeleton was

discovered, to which the stray rib properly belonged.

‘Both were

obviously those of young persons; and, as the garden is in the

neighbourhood in which lived the notorious Bishop and Williams, who

were executed for the murder of the Italian boy, the gossips of that

locality at once came to the conclusion that they were the remains of

some unknown victims of those murderers.

‘Bishop and Williams were,

however, disciples of Hare and Burke [sic], and carried their victims

to a better market; the popular supposition is therefore improbable.

At the inquest, the researches of the police may perchance reveal

somewhat more of this mysterious affair.’ Alas not: nothing more appears in the records about these Bethnal Green bones.

A few years ago, I was giving a talk in Stepney about the Italian Boy case, and afterwards a man came up to tell me that he had spent his working life on demolition and construction sites, mostly in the East End. He operated the machinery that drills down into the soil in preparation for pile-driving. As the earth came up to the surface, he said, it was not so very unusual for old human bones to be in among the soil. This was on sites where no cemetery or churchyard had ever been.

My own thoughts about this are that

perhaps some non-Church of England Protestants may have been deciding to bury their dead within the precincts of their own homes, rather than consign them to the burial grounds of a church with which they had no allegiance, no doctrinal sympathy, and to whom they would not wish to pay burial fees. To whom, in fact, many Non-Conformists/Dissenters felt significant hostility.

The building-site man and I were interrupted in our conversation by another attendee, and when I turned back to continue, he had disappeared (like someone in a passage by Thomas De Quincey). I later established that he wasn’t a member of the history society who had asked me to talk, so I have never been able to find him to explore the subject further with him.

This picture, from the Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archive collection, shows the excavation of the garden of 3 Nova Scotia Gardens, Bethnal Green, as the Italian Boy murder investigation got under way. No bones were found, of course, but plenty of physical evidence of the killings that had taken place here. THLHL&A, 277 Bancroft Road, E1 4DQ, tel: 020 7364 1290. localhistory@towerhamlets.gov.uk.

19/5/2013 James May, Resurrection Poet

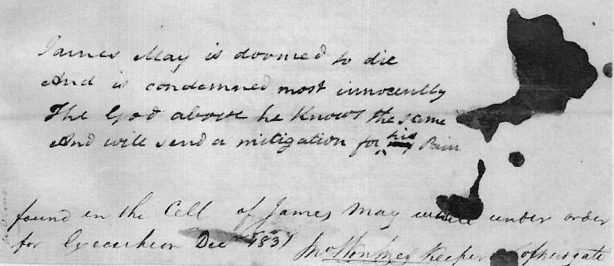

While awaiting execution in Newgate Gaol, having been condemned for the murder of the Italian boy, resurrectionist James May penned this poem. It was snaffled away by the prison governor, John Wontner.

‘James May is doomed to die/And is condemned most innocently/The God above he knows the same/And will send a mitigation [pardon] for his pain.’

7/5/2013 Food safety in 1828 and 1847

Not quite the eating of horsemeat, but not that far off, either . . .

● In an 1847 pamphlet entitled ‘Smithfield and the Slaughterhouses: A Letter to the Rt Hon Viscount Morpeth MP by a Liveryman of London’, the Liveryman alleged that at Smithfield, ducks, pigs and so on were fed on slaughterhouse refuse. Smithfield butchers classify meat as ‘slaughter house’, ‘knackers’ or ‘dust-heap pork’. ‘Let the reader reflect on the bare possibility of having partaken of the flesh fed, perhaps, on the foetid refuse of a diseased or glandered horse. . . ’

● Adam Armstrong told a Select Committee that he had seen a cow’s cacase hanging up at the Bear and Ragged Staff pub, on the north-east edge of Smithfield market, that was running with yellow slime, where there should have been fat. This was an example of ‘cag mag’, said Armstrong, which was the poorest-quality meat, unfit for humans to eat, but which would later be taken under cover of darkness to be made into sausages.

‘Select Committee on the State of Smithfield Market’, 1828, p25

30/4/2013 The Bishop and Williams recipe book

Some of the drinks my alcoholic anti-heroes put away during their treks around London sounded frankly delicious to me. Here are a couple of tap-room tipples you could enjoy in 1831:

Egg Hot: boil up in a saucepan one quart of strong ale, some sugar, cinnamon and a dash of lemon. Remove from the heat and add a glass of cold ale. In a jug, beat 6-8 egg yolks and add some sugar and nutmeg. Pour the ale into this jug and stir.

A variant was Egg Flip:

add extra eggs and cream to the above and then thrust a hot poker into the jug, making it bubble and giving a more bitter and burnt flavour.

For extra strength, add one or two glasses of gin and/or rum, as preferred.

If you really wanted to get out of it (or get somebody else out of it, in order to rob, sexually assault or burke them), ‘locus-ale’ was beer that had had laudanum (liquid opium) added in. The act of spiking someone else’s drink in this way was known colloquially as ‘to hocus’ or ‘to locus’ someone.

20/4/2013 Jerry Cruncher, Mrs Lovett and the mysterious Shire Lane area

This revolting case was reported in the North Wales Chronicle of 20 May 1830, although it was a London court hearing. Resurrection men were the most hated section of the community, and this report helps to explain why.

‘A well-known pilferer of graves, named Clarke, was tried upon an indictment, charging him with having stolen the body of a dead child, aged about four years, which had been under the care of a nurse named Mary Hopkins. The facts which came out in evidence are as follows:

‘the deceased was the daughter of a woman of the town, residing in Shire Lane [off Fleet Street], and had been kept at the nurse’s lodging, which was in the same neighbourhood. She died on a Friday, and Clarke, whose ears were described as “quick to the toll of the passing bell”, paid the nurse a visit the next morning, under pretence of hiring a cellar under the house. He took occasion to notice the poor woman’s [the nurse’s] son; he said it was a pity to see the boy idle, and that he should have immediate employment, and called again with evidences of still stronger interest in favour of the family. “By the way,” said he, “I understand you have had a death lately.” “Yes, sir,” said the nurse, “a poor little girl is departed.” “Poor little dear,” cried the snatcher, “I should like to look at the little innocent.”

‘He was forthwith led into the front parlour, where the body lay in a coffin, and observing that its position was favourable to his intention, he sympathised with the nurse, and said, “We must all come to this sooner or later,” and then he went to get a half-pint of something to comfort them. The nurse disposed of a glass, which presently set her in a profound sleep, and when she awoke the body of the babe was gone. It appeared that the snatcher, after having quitted the house, as if for good, returned, and opening the parlour window, hooked out with a stick the corpse of the child, and went off with it towards a market that is open at all hours, near Bridgewater Square [near the Barbican].

‘However, a police officer, who knew his trade, laid hands upon him, telling him that he was wanted. The snatcher then threw down the child and took to his heels, but was apprehended and lodged in the Compter. The nurse proved the identity of the body. Upon her cross-examination by Mr Payne [JP], she stated that the mother had not been to see the deceased for four or five days before the death. The jury returned a verdict of Guilty, but some of them audibly spoke of recommending the prisoner to mercy, but made no appendage to that effect. The Recorder sentenced the prisoner to be imprisoned for the space of six calendar months.’

Six months was the maximum sentence for illegal possession of a corpse

– a leniency that infuriated the public, when property crimes were so comparatively harshly punished.

Shire Lane, where the theft of the child’s body took place, was one street west of Bell Yard; the latter is still there (its eastern side intact, at least) but Shire Lane disappeared in the 1860s for the building of the Royal Courts of Justice, which obliterated a huge swathe of run-down Tudor/Stuart housing on the north side of the Strand/Fleet Street.

Bell Yard is course the site of the fictional Mrs Lovett’s Pie Shop – could the Clarke case have contributed something to the grand guignol tale concocted by Thomas Peckett Prest in his String of Pearls (1846-7), which introduced Sweeney Todd? Bodies to be made use of for financial gain?

What’s more, Dickens’s bodysnatcher Jerry Cruncher, in A Tale of Two Cities, had his day job as a messenger for Tellson’s Bank, near to the Temple Bar, at the southern end of Shire Lane. Sitting on his stool at the bank’s entrance way, he would listen out and watch for signs of a funeral; like Clarke, whose ears were “quick to the toll of the passing bell”. Jerry Cruncher’s night-time job of stealing corpses from graveyards is described in the novel as ‘fishing’ – and fishing is the image left by Clarke hooking the child’s body out of the window with a stick and hauling it away.

The following newspaper report reveals the area as awaited its demolition:

‘A Desert in the Heart of London’,

Sunday Gazette, reprinted in The Times, 12 November, 1866

‘The extensive and complicated network of lanes, courts and alleys covering the area bounded east and west by Bell Yard and Clement’s Inn, north by Carey Street, and south by the Strand and Fleet Street, lately containing a population more numerous than that of many parliamentary boroughs, is being fast deserted. A few of the winding thoroughfares are not yet disturbed, but several of old and worse than equivocal notoriety, and in which, a few weeks ago, passage was rendered somewhat difficult by the human swarms whose modes of existence are among the unsolved “social mysteries”, are now almost uninhabited, only a house or two remaining, in exceptional cases, where a brief extension of term has been granted.

‘Massive padlocks guard every door. The glass on the first and second floors has been smashed in by unforbidden missiles discharged as parting salutes by the more juvenile emigrants, and the grimy, stooping, unwholesome buildings wear an aspect of weird gloom, contrasting strangely with their recent animation, when every doorway and window arrested passing attention with grotesque and sordid samples of human nature.

‘The ground taken by the . . . new law courts and offices includes nearly 30 lanes and passages, the names of some of which will be familiar to all who have made acquaintance with the topography of London. Among them is Clement’s Lane [sketched below, bottom pic]. Here still stand some old houses, the very peculiar, perhaps unique, character of whose construction is worthy a visit.. . Then there is Bell Yard, the seat of newsvendors, law booksellers and printers. . . Next comes Upper and Middle Serles Place, with Lower Serles Place, formerly Shire Lane. Ship Yard, mentioned more than once in the chronicles of 17th- and 18th-century roysterings; Crown Court, a dilapidated passage. . . with its noisy and dangerous neighbour, Newcastle Court...’

Historian H Willoughby Lyle wrote in 1950 of the Royal Courts of Justice clearances, and stated that Shire Lane (above right) had been a foot passage only, and in the time of James I had been called Rogues Lane. In 1845 it had had its name changed from Shire Lane to Lower Serles Place. The nearby Ship Yard, home of the Ship Inn, had had a bad reputation and was also home to a pub called The Smashing Lumber – a counterfeiters’ den. Butchers’ Row was also known locally as The Straits of St Clements, and used to be full of slaughterhouses. In 1604-5 the Gunpowder Plot was hatched in the Duck and Drake inn on Butcher’s Row.

In Boswell Court (above left), which was reached by stairs, had stood the last of London’s charleys’ (night-watchmen’s) sentry boxes.

Lyle, An Addendum to King’s and Some King’s Men, Lyle’s original book of 1935 about the environs of the first King’s College Hospital.

7/4/2013 ‘I was one of them, Sir’: retired resurrectionists

Dr James Fernandez Clarke (1812-1875) was just nineteen when he was present at the post-mortem of the Italian Boy, in November 1831. The experience unnerved him, as he wrote in his autobiography; he also went on to recall the dying out of the resurrection trade with the passing of the Anatomy Act, shortly after the Bishop and Williams case:

‘Nothing could have been more unsatisfactory and disgraceful to us as a civilised nation,’ wrote Clarke. ‘The outrages against decency, the misdemeanours, which the law was compelled to wink at, continued long after the necessity for a change had been demonstrated. The low ruffians who acted as “resurrectionists” were, to a certain extent, necessary evils, but they were the lowest of the low, and would stop at nothing to obtain their ends. He who recollects the passing of the Anatomy Act will remember how, for three or four years after, he was frequently in the evening waited upon by an ill-looking rascal, who solicited assistance. “I was one of them, sir,” he would say, “whose lost their work by the Anatomy Act.”

‘One could scarcely refuse such an appeal, seeing how much we were indebted to the applicant. This kind of application died out in time, and it is now probable that not a single “resurrectionist” is in existence. But it is awful to contemplate the amount of crime of the worst kind which must have been committed. Wretches who held human life as a mere marketable commodity must, to have lived, committed many murders.

‘Even now, the Anatomy Act is imperfect. The inspector should have more power conferred upon him, so that the supply of bodies, under proper regulations, should be equal to the demand. No one could have carried out his duties with more energy and prudence than the present inspector; but he is hampered in his efforts, and thwarted in his endeavours to make the supply sufficient. Of late, however, I am glad to say there have been fewer complaints of a deficient supply than in former years.’

Autobiographical Recollections of the Medical Profession by JF Clarke (1874), pp103-4.

23/3/2013 Never mind Jane Austen. . .

. . . The Diary of A Resurrectionist, 1811-1812 is a window on to the world of the Regency – a personal record written BY a bodysnatcher, rather than ABOUT one. The diary was presented to the Royal College of Surgeons of England by Sir Thomas Longmore in the mid-19th-century; Longmore himself had been handed the written account by resurrectionist Joshua Naples, who had supplied famous surgeon Sir Astley Cooper (1768-1841) with corpses. Longmore had been assisting in the writing of Cooper’s biography and Naples had been one of Cooper’s most trustworthy suppliers.

Here’s a taster of Naples’ working life:

Friday 7 Feb 1812, ‘Met together me & Butler went to Newington, thing bad.’ [ie putrid]

Tuesday 25 Feb 1812: ‘The moon at full, could not go.’

‘Rules for finding the moon on any given day.’

Tuesday 11 August 1812 ‘At night went to Hoxton, 1 Large Yellow Jaundice sold at Brookes [anatomy

school].’

The original diary is still housed at the Royal College of Surgeons, but the Museum of London has made an interactive touchscreen exhibit of it as part of the ‘Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men’ show (ends on 14 April). It’s a unique snapshot of Regency life – and not an Empire-line dress in sight.

20/3/2013 Of Pet Shop Boys and priests

This pastor chap (http://itself.wordpress.com/2013/03/15/lent-5-sermon-the-resurrectionist/) blogged last week about how The Italian Boy had set him thinking about Lazarus, Lent, death, re-birth, incense, biblical undertakers, Nietzsche, Easter, the Kingdom of God. He also embedded in his blog the Pet Shop Boys track ‘The Resurrectionist’, which my book inspired.

People were very kind about The Italian Boy when it came out, but as rewards go, ‘The Resurrectionist’ really was for me the ne plus ultra. (Pretentious? Moi?) Your favourite band writes a song about your book: I could retire happy. (I didn’t – I’ll slog on till I drop.) ‘The Resurrectionist’ is on the 2012 double album Format, or as the B side to the 2006 single ‘I’m With Stupid’, or as its own MP3 download, obv.

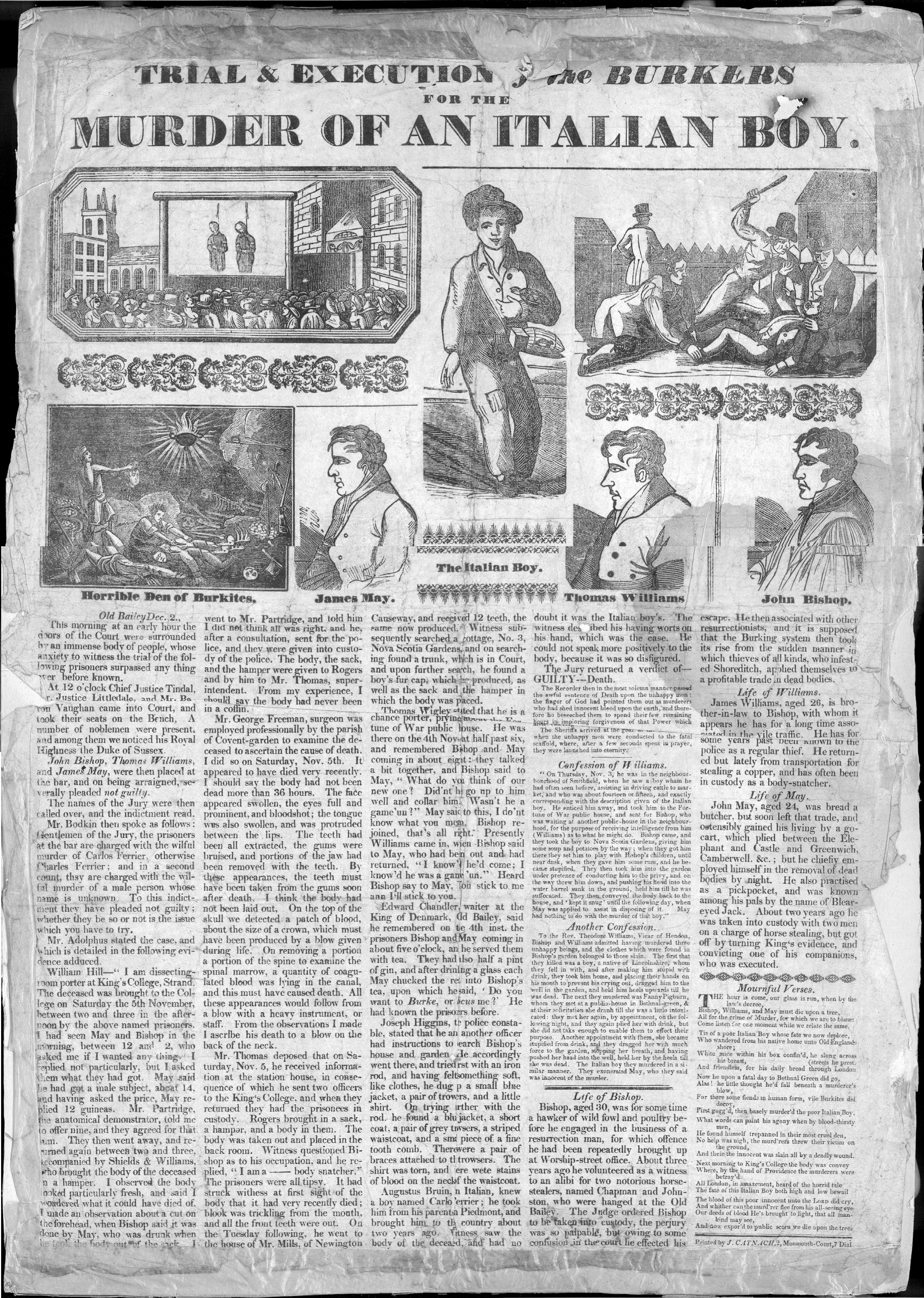

16/3/2013 Hot off the press. . .in December 1831

This fantastic original broadsheet was a very welcome present from a reader. Barry Trowbridge, from Kent (who, like me, worked as a newspaper sub-editor), wrote to me asking if I would like to relieve him of this item, which had lain around his family home for years. ‘For as long as I can remember, my family has owned this poster, or broadsheet, relating to the murder featured in your book. It forms the backing to a photograph of my grandfather and has been gathering dust under a wardrobe. I would like to pass it on to you, as someone with an interest,’ Barry wrote to me.

‘It was printed by J. Catnach of 2 Monmouth Court, 7 Dials. [Catnach was a hugely successful purveyor of this type of cheap, one-off, catchpenny print.] It is similar to the broadsheets on pp241-3 of your book.

‘There was always family talk about “the Italian Boy” case. As for its history in relation to us, I’m afraid I don’t know any more than that.’

Barry was adopted, and his adoptive grandfather had died before Barry was born: the photograph (below) shows a rather severe-looking man with dramatic features. It is tempting to speculate that his grandfather’s own antecedents either knew the killers, or that he was descended from Italian immigrants; but there is nothing to go on in attempting to forge a link between the man photographed on one side of the piece of board and the broadsheet pasted on to the reverse.

Like so much in the Italian Boy case (and in the history of broadsheets, for that matter), this item is packed with curiosities. Catchpenny prints often re-used stock imagery cut on to wooden blocks and so the pictures often bear little relation to the crime that is being reported on. With the Bishop and Williams case, for instance, many broadsheets simply re-used their Burke and Hare woodcuts of three years earlier, showing suffocation as the modus operandi. Above, James May and Thomas Williams as depicted by Catnach are simply the woodcuts of other previously reported criminals; but the John Bishop image is very similar to a sketch of him that had appeared in the Sunday Times report of the muder trial at the Old Bailey. Did Catnach shell out a little money to capture Bishop in a freshly cut new block?

The murder as depicted (top right) looks to me as though is has been taken from accounts of the 1824 murder of William Weare by John Thurtell and associates. (Just a guess – there are other 1820s crimes of which this could have been a representation.) The victim here is hardly a boy, and what on earth is that weapon? No weapon was used on the Italian Boy.

Similarly, the ‘Horrible Den of Burkites’ image has been imported direct from some other genre altogether. The house where the murder took place had no cellar at all, and no pile of skeletons (the point of murder-for-anatomy is to sell a fresh corpse for money, not to keep it stashed away until it became bones); John Bishop’s house had no holy grail appearing in mid-air, no decapitated heads being brandished.

I know, I sound as though I’m not grateful – that I’m sneering. But I really am thrilled with my new possession, Barry. Thanks ever so.

For further reading on the world of the early 19th-century broadsheet:

Thomas Gretton, Murders and Moralities: English Catchpenny Prints, 1800-1860 (1980); and The Story of Street Literature by Robert Collison (1973).

The most significant collection of 19th-century broadsheets and other print ephemera is to be found at the St Bride’s Printing Library, off Fleet Street, http://stbride.org/library/contact

27/2/2013 Problems With Boys

In 1828 a Select Committee was set up to consider juvenile crime. One of the people who came forward to give his opinion was Reverend Robert Black, Honorary Secretary of the National Schools of the City of London. On 19 March he told the Committee of his experience with troublesome schoolboys: ‘It has fallen to my lot to watch the career of many [school-leavers]; but out of some thousands, it is difficult to keep your eye upon more than a hundred of them. . . They have generally risen in society and become very respectable, either mechanics or servants. Or I have known many of them go as writers to attornies, and make a very good living by it. . .

‘Boys of bad character and bad habits are not likely to remain with us; we have had some experience in that way; in some few instances we have been enabled to retain some boys, and reclaim them, but those who have formed bad habits will not remain with us. They will play truant so much that we are obliged to expel them for the sake of keeping up the discipline of the school; and the parents, when they are summoned, appear very careless about it... It happens more frequently than we could wish.

‘There is one class of boys that we have not been enabled to bring to our schools yet, and that is the very lowest, who are without shoes, and are generally so raggedly clothed that the excuse is with many that they have no shoes to come to school in. I have been too frequently in contact with them; I see them about; they are a very dissolute description of boys, and very unruly in every respect; they are boys that take a delight in annoying our schools; and in the neighbourhood of Shoe Lane [Holborn] in particular, I have been obliged to have two of them more than once before a magistrate, for having broken our windows, merely out of sport. It is that description of boys that I apprehend are chiefly brought before magistrates. I am afraid it is a very numerous class.

‘We are as tender of corporal punishment as possible, but sometimes we correct him by keeping the boy longer in school or by disgracing him in the eyes of his school fellows. . . which is generally very effectual to bring him to his senses. . .We endeavour to excite in their parents’ minds a desire to co-operate with us, and the first thing we say to them is, “We trust you will take as great an interest in them as we do, and that you will see that good effect is produced”. The parents are summoned to attend the committee on the admission of their children; and one point that is enforced upon them is, that they shall see that what is learned at school is attended to at home.’

![]()